Angle/ Angel 1: Craft Notes

Abstraction is a technique to quiet the Imagination that blocks grace

The Imagination is continually at work filling up all the fissures through which grace must pass.

-Simone Weil, “Imagination Which Fills the Void”

A question: how to write fiction (a work of imagination) that leaves fissures for grace to pass.

How much should be filled and how much should be left open?

The question of the scaffold.

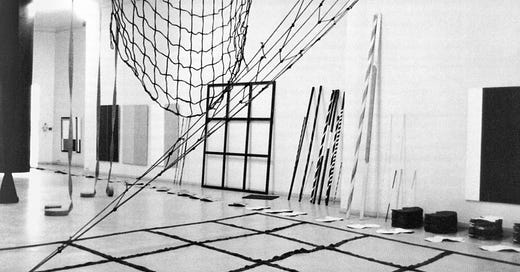

I refer back often enough to 2014, the year of electro-convulsive therapy and dramatic urban development in Nashville, and I’ll do it again. The skyline was filled with scaffolded buildings and cranes which were composed of scaffolding. These frames looked skeletal. From a distance, a building under construction is hard to tell apart from a building falling apart. This scaffolding created all sorts of odd angles cutting through the sky. I became fixated on these angles.

Since then, I’ve been trying to figure out how to write that skyline and those angles. Sometimes that literal skyline. I’ve written some variation of the above paragraph so many times and still haven’t quite landed on what I want. I’ve attempted at a novel set in Nashville with an urban development plotline. It was a disaster.

Maybe these attempts have been too literal.

So this is the question that I’ve been working at for years: how do you write the scaffolding? How do you write those angles?

What does writing that learns from that skyline look like?

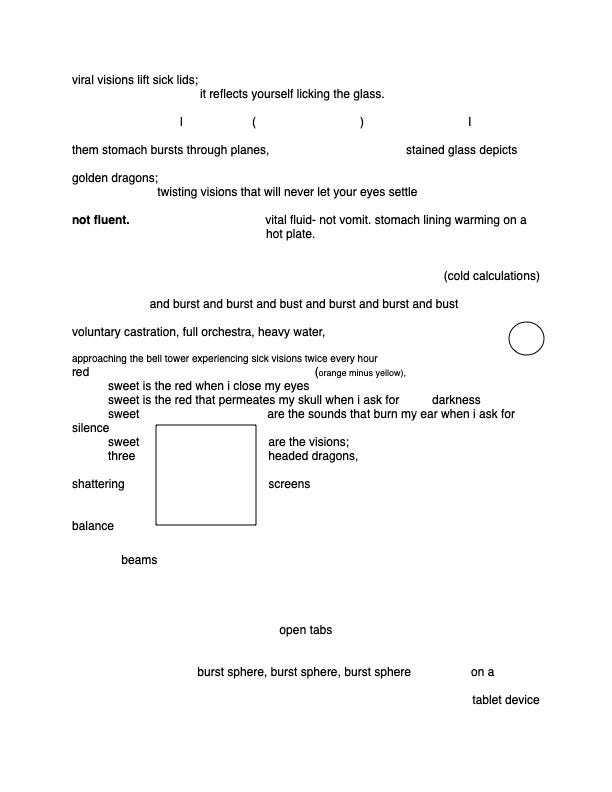

Around that time, I was writing a lot of abstract poetry. I was frustrated with language and the inarticulations of depression and ECT. The poetry I was writing then was a poetics that reduced shapes and sounds, stripping language of literal meaning. In part, this was because literal meaning was so out of reach for me. I think there was also a violence in it, anger, an attempt to take some sort of revenge against language and articulation.1 I was also making using a lot of empty space at this time. The empty space allowed the words to cut into the page at odd angles. The empty space allowed for the words to act as odd, violent, angular shapes.

I was not thinking in terms of leaving the empty space as a clearing for grace or even meaning to appear.

The poetry was abstract. However, in its abstraction, the poetry was somehow more literal. I would sometimes use the “technique” of “drawing” lines across the page, often crossing these lines, literal lines intersecting with other literal lines. As poetry, this was very abstract. As a depiction of a scaffold it was quite literal. The angles were literal. (To be clear, this was not deliberate. At the time I wasn’t thinking, ok, the shape of this poem will depict the Nashville skyline. It is only looking back on it now that I realize this.)

A visual depiction is less abstract than a depiction through language. Words are already symbols. Writing is inherently an abstracting. A word that is stripped of its symbolic meaning is not abstracted, it is made literal. The only meaning it has itself, its shape and sound. It does not mean that shape and sound, it is that shape and sound.

The more abstract writing is the more literal it is and in that way it is less abstract.

The Imaginary will eat away at you. Your thoughts will eat away at you and create shadows where there are none. Ideas are the shadows on the wall.

Abstraction is a technique to quiet the Imagination that blocks grace.

Another way of thinking about this: the architecture of a story. The angle formed at the convergence of two plot-lines. The single point that two characters occupy together briefly, and the separate lines that got them to that point. The space around those lines.

Those lines are the imaginary, the fictional story being told. The empty space between those lines, the angle is the truth the fiction scaffolds. Writing at angles, with scaffold, allowing for negative space. The negative space would be there with or without the lines around it, but lines help you understand that negative space, to frame all that negative space that is the real. The marks on the page, the imaginary, scaffold this negative space, give it context.

The angles of the plotlines of a realist novel are more conceptual than the highly literal angles in the Support-Surface piece that I opened this essay with2.

An angular novel is one filled with characters. The third omniscient affords opportunities for angles that the first person, set on a straight line, doesn’t. The realist third person omniscient novel as a series of angles. Dickens as a Futurist painting (for example, Tullio Cralli’s Nosedive on the cover of Pynchon’s Against the Day.)

I use the term angle instead of intersection very intentionally. Intersection has been over-burdened. Overused. Everything is sitting at the intersection of something else and intersectionality remains a hotly contested site in the culture war, one I don’t want to engage in in this specific moment. I would like to give “intersection” a well deserved rest.

More than that though. An angle is different than an intersection. The difference is small but important. An intersection is the singular point where two lines meet. It is the point where both lines are present. An angle is the space between the intersections. Around the intersection. It is the empty field of the graph. Technically, an absence. The clearing.

I am fixated on the wordplay of angle and angel. I am interested in the angel that can appear in the angles. The fissure through which grace must pass. The cracks where the light comes in.

At least one side of a prism must be angled. As light passes through a prism, it refracts; the straight line becomes an angled one, and white light is separated into different colors.

It is the angle that reveals the brilliant rainbow latent in the blank white light. (An angel appears.)

There was a bathroom next to my bedroom at my parents house. It jutted out from the rest of the house ever so slightly. The two walls, the bathroom and my bedroom, met outside at about a 45 degree angle. The space between them wasn’t very big, maybe a couple of square feet (it was a triangle.) I remember one day looking out my bathroom window and seeing a strong ray of light suspended in the angle, in the space between the two walls, and I remember looking down to see the ground below, and I knew right then that I that whatever storm had overtaken me for the past two years had passed. Radiating from that angle, that space, the rest of the world slowly started to return to me.

In a recent article in the Yale Review, Percival Everett writes about his quest to write an abstract novel. Of this quest he says

I believe that I should be able to construct such a thing, an abstract novel. Given that the constituent parts of my art, namely words, are representational, the problem is obvious. Still, I believe that I should be able to make it. The other obstacle is that I have no idea what such a thing might look like.

and that

I believe that the closest I have gotten to the abstract novel I want to make is Wounded, a novel that people tell me is realistic, naturalistic. What they mean is that the story moves ahead with a narration that offers a series of events that the reader can see, that there are no structural impediments to the meaning the reader is seeking, all while being offered a severely editorialized world with 90 percent of what people will actually say missing and a current that pushes single-mindedly toward a goal. Hardly “real.”

Realism is abstraction, abstraction is literal.

(compare to Cusk’s movements in the opposite direction— away from character, finding fiction to be “fake and embarrassing”. consider then, in light of her Outline trilogy, the relationship between an outline and a scaffold. what is the possibility of angles w/o characters?