Thus always unto tyrants: dramaturgical notes towards an unrealized play

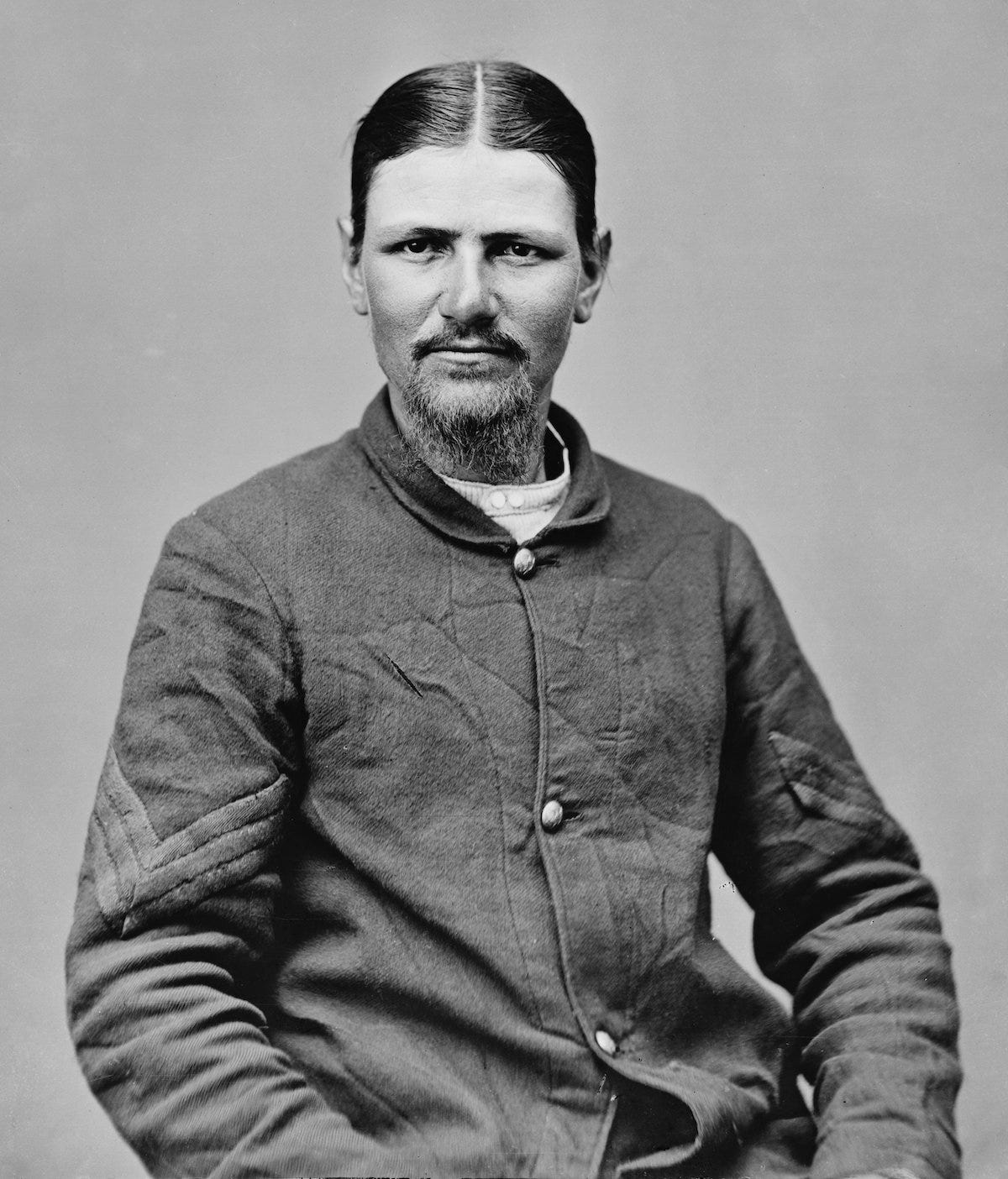

Boston Corbett, the man who killed john wilkes booth

I’m writing a play, or trying to. At this point it is more of a spiraling dramaturgical project. I’ve been working on this, off an on, for five years. The biggest obstacle I’ve found in writing the play has been that I don’t know how to do it, in that I’m not all that familiar with theater as a medium and scripts as a form. This project, however, has to be a play, for reasons that I want to talk about in a little bit. I don’t know how to write plays but I know how to research and rabbithole. At this point I have plenty of dramaturgical notes and I want to use this space for a small running series of this dramaturgical project as it hopefully develops into a play.

The play is called Thus Always Unto Tyrants. The titled comes from the phrase that John Wilkes Booth shouted after assassinating Abraham Lincoln, “sic semper tyrannis”, quoting Brutus1 when he killed Julius Caesar. (Booth was a well known Shakespearean actor and had performed in Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar a number of times.) Sic semper tyrannis is also the state motto of Virginia, which housed the capitol of the Confederacy and was the state where Booth lived and worked for much of his life. As I’ve been writing the play, I’ve been drawing from these two sources of the phrases, Shakespeare and Virginia (in the form of things like the writings of Thomas Jefferson2.) But before I get ahead of myself I want to outline some key details of the play.3

The play is about Boston Corbett, the man who shot John Wilkes Booth. He’s a fascinating character to me. A devout but itinerant street preacher, Corbett practiced as a hatmaker by trade. The exposure to mercury in his work as a hatmaker drove him crazy (mad as hatter...) He grew his hair like Jesus and moved around Northeast following the hatmaking trade and congregations. At some point, he castrated himself so as to avoid the temptations that come with an uncastrated body. Eventually the war came around and he joined the Union army, where he was known as a good soldier but one who wore on the patience of some of his fellow soldiers with his insistence his rigid devotion Christianity. At one point he was court martialled for reprimanding his commanding officer, Daniel Butterfield, the composer of Taps, for swearing. At another point, he dramatically fought off six or seven rebel soldiers before eventually being captured. Later in his life, struggling with the celebrity of killing Booth and his health, Corbett would becoming increasingly paranoid. He moved out west and started a homestead. He never went anywhere without a gun and his neighbors reported that he had a large stash of guns in his house. After losing his security guard job at the Kansas state legislature, he was committed to an insane asylum. He escaped from the asylum; this was the last reported siting of him.

Why a play? I’ve considered writing this project in prose— I’m much more comfortable with it— but there are a couple of reasons this project will only work as a play. John Wilkes Booth was a Shakespearean actor, and his father and brother were the most respected Shakespearean actors of their respective generations. (Booth was considered a good actor, but one who relied on his natural talents and good looks and failed while failing to develop his technique). The play draws directly from this fact, and it exists to be in conversation with theater, especially Shakespeare. Much of the dialogue is woven together from Shakespeare and quotes from Corbett and Booth, among others, and this non-naturalistic kind of dialogue makes more sense as a play, which allows for a heightened sense of reality in a way that a novel wouldn’t. A play allows for more dialogue in general than a novel, and more importantly maybe, it discourages other kinds of writing. In fact, a play is all dialogue. The only words that can be transmitted to the audience are ones that are spoken on stage. There is no ability to rely on a narrator who can tell you what the characters are thinking or give a round up of historical facts. This provides a challenge but also a necessary limitation. The only historical references, the only references to my dramaturgical notes, that I can make are ones that come through dialogue (and, to an extent, later on hopefully, stage design). I have to keep it reigned in on the allusions and references, even as it gets wilder in other ways. Tautologically, theater is theatrical. There is room for performance. Performance is thematically important to the text, and something of this would be lost of this thematic consideration in prose. I think this would fall flat as a historical fiction novel. As a tragedy4 engaged in conversation with other tragic theater and using history as its material, there is a chance for it to succeed as something larger than life. I don’t want the techniques of a novel. I don’t want to get inside Corbett’s head. I want the distance and artificiality of theater.

With Corbett as my starting point, I’ve been able to write in a number of different directions. The challenge for the next stage is condensing all of that into a single play. He is a cipher, and that allows me a lot of freedom when writing about him, and writing about the things he came in contact with. He is a fascinating figure in his own rights, and I hope, as this project progresses here, to upload a post on a deeper look into his bio/ character “notes”. He also feels like a good metaphorical figure for a lot themes I have been working with and a lot of themes that feel relevant right now (assassination, for example).

Corbett provides me a way to explore America’s pathological and incoherent violence. Corbett, later in life, became increasingly paranoid. He hoarded guns and never went anywhere without one. He got into multiple altercations where he fired or brandished his guns, including in courtrooms (where he was on trial for shooting his gun to warn some kids off his property) and at state legislatures. After the war, Corbett continued to preach, and he remained devout in his Christianity. That mixture of religious fanaticism and guns is quintessentially American.

That being said, I don’t think I know what Corbett’s politics are. They don’t track neatly onto right/left. Guns and religious fanaticism are usually a part a broader right wing valence, at least in contemporary America. However, those things, guns and religious fanaticism, are secondary characteristics; they often accompany a right wing ideology, but they don’t constitute an ideology itself.

It wouldn’t be fair to say that Corbett had no ideology. He was a man of great personal conviction. As this project unfolds, I think it will show that Corbett had more personal conviction than most people do, probably more than you. But that conviction is idiosyncratic. Strange (he is above all a very strange man). Unto himself. He was, by all accounts rigorously honest. He didn’t swear. He despised slavery, but for religious, not political, reasons. (Everything is political, everything except for politics, which don’t exist.) There is only so much use in trying to map a political schema on something so mercurial. It’s trying to get into the head of a madman.

But that’s the point. A madman is a better representation of American political life than Booth or Lincoln. A crazed loner with a gun. He is idiosyncratic, one of one, but he is also representative of something. American politics are not coherent, they are a mercurial fever dream of violence and retribution.

Full name- marcus junius brutus. JWB’s father was named Junius and was renowned as the best Shakespearean actor in America.

The one about the tree of liberty and the blood of tyrants, for example. If tyrant is used by an early American politician I flag it.

Thus alway unto tyrants, as a phrase has proven a great guiding light to explore themes of retributive violence. It’s taken me far afield, such as reading the Oresteia cycle, a trilogy of ancient Greek tragic plays deeply concerned with cycles of vengeance. However, no matter how far afield I get, how lost in the weeds down the rabbit hole, thus always unto tyrants is a helpful guiding post to return to the center of the project.

The ancient and classical and shakespearean tragedies were historical, but you don’t really think of them like that.

The most important thing is to have a project.

A lot of people don't understand that.

We stan a rabbit hole fr 🫡